You are reading:

You are reading:

28.05.24

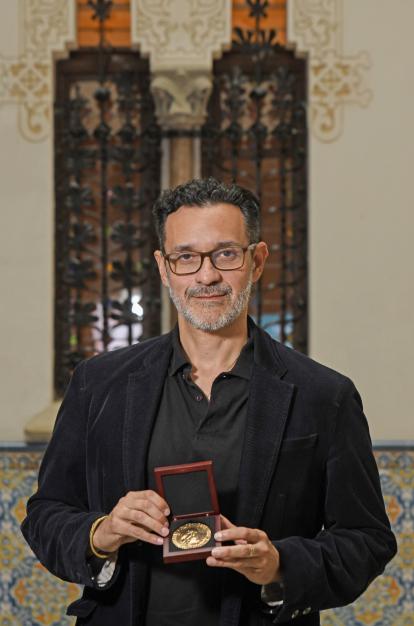

8 minutes readCarlos Umaña (Costa Rica, 1975) is a physician and activist. He is a member of the steering group of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, which was awarded the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize for its work to raise awareness and build social and political support for the adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Umaña, who co-chairs International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, took part in a conference organised by the Social Observatory of the ”la Caixa” Foundation at CaixaForum Macaya.

Your awareness of the effects of nuclear weapons began after visiting Hiroshima. What happened on that trip?

In 2002 I went to Japan to attend a course on epidemiological research with the Costa Rican Ministry of Health, and during our stay we were taken to the Hiroshima Museum. At that time I didn’t know much about the effects of nuclear weapons, but there was something that had a profound effect on me. It was a drawing by a survivor, almost cartoonish, of some little girls emerging from the rubble in agony, begging for water and calling for their mother. That stayed with me, I still remember it clearly.

When did your activism begin?

Ten years after my visit to Hiroshima. I had given up medicine to study painting and sculpture, but a colleague told me that International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War existed and that she wanted to open a branch in Costa Rica. Together we set it up, and within a few months we had organised a major event at the presidential palace, where the then president, Laura Chinchilla, committed herself to banning nuclear weapons.

Almost 80 years after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, is there still a risk of nuclear war?

Experts say this is the most dangerous moment in history, not just because of the likelihood of it happening, but because of the impact it could have. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, responsible for the so-called «Doomsday Clock», which symbolically measures how close we are to full-scale nuclear war, has declared that we are 90 seconds away from such a scenario. To put this in context, we were 12 minutes away in the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

How has the conflict in the Gaza Strip affected this threat?

Israel has not publicly acknowledged that it has the atomic bomb, but it says so indirectly. In fact, one minister has repeatedly said that it should be used in Gaza. This is very worrying, because it not only relativises the suffering of innocent civilians, but also shows that it has no knowledge of the effects of this type of weapon, which cannot be controlled and knows no limits. On the other hand, the conflict is destabilising the Middle East and could lead to the emergence of a new nuclear state, as the International Atomic Energy Agency has described Iran as being one technical step away from developing the bomb.

And the situation in Ukraine?

In this case, Russia has used its possession of nuclear weapons as a tool of coercion. It explicitly stated that if any country dared to intervene in the conflict, it would face consequences like there have never been before. In the context of war, where there are countries making such threats, it’s easier for a false alarm to be misinterpreted as a real attack. The risk of miscalculation increases.

In fact, the UN Secretary General said in 2022 that the world is «one misunderstanding away from nuclear annihilation». What did he mean?

One of the most worrying risks is the increasing possibility of accidental detonation. Early warning systems are becoming more interconnected and automated, and are more vulnerable to technical and human error, as well as cyber-terrorism. Of the approximately 12,500 warheads in the nine nuclear-weapon states, some 2,000 are in a highly operational state, meaning they can be detonated within minutes. The early warning systems that decide whether or not to launch a bomb as a counterattack have been wrong many, many times. And they’ve done so because of confusions as banal as those caused by a flock of geese, a weather balloon or a storm cloud.

You said that the effects of atomic bombs are uncontrollable. What would happen in the event of a nuclear war?

If detonated in a major city like Washington or Moscow, a modern atomic bomb could cause tens of thousands of deaths instantly, hundreds of thousands of injuries and victims of acute radiation syndrome, which is one of the most painful things a person can suffer because it breaks down vital organs. It would also cause chronic illnesses and a very high incidence of various types of cancer and birth defects, even in future generations, in the children of apparently healthy people. Now, if we’re talking about full-scale nuclear war, we’re not talking about one detonation, but several. That means millions of dead and injured. On the other hand, the ozone layer would be destroyed and a huge amount of soot would rise into the stratosphere. This would block the passage of sunlight, making the world a much darker and colder place, and many ecosystems wouldn’t be able to survive such drastic changes. It would be the end of many, many species, the end of our civilisation and probably the end of humanity.

Starting a nuclear war seems suicidal for any country. Why do states still have these weapons?

Everyone understands that nuclear weapons are made not to be used, because it’s virtually impossible to use them without someone using them against you. Their value lies in the threat of their use. And the paradox is that, for it to work, that threat must be credible. It’s an absurdity that we live with without thinking about it.

How can it be legal to possess atomic bombs?

It’s not legal actually, especially under international humanitarian law, which is essentially the law of war. All weapons of mass destruction are illegal, but there was no explicit ban on nuclear weapons until the 2017 Prohibition Treaty. The problem now is the misinterpretation of the law, which is made on the basis of convenience, and the lack of universality. If a regulation is not universal, it will not be applied, which is why we’re in this stigmatisation phase, in order to achieve its application.

What exactly is the stigmatisation promoted by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons?

As a number of countries have not joined the Prohibition Treaty, a strategy of «moral condemnation» is emerging, which makes these weapons unacceptable to the public. This is a change that’s been effective throughout history, for example in the abolition of slavery and other types of weapons such as chemical or biological weapons. It was also the case with landmines and cluster munitions. The United States stopped producing them not out of conviction, but because it ran out of buyers and investors, because of the global stigma against their production.

What do you think of the argument that nuclear weapons prevent major conflicts?

It’s completely absurd and naive. When the atomic bomb came along, many people, including some pacifists, thought it would prevent the great powers from attacking each other. But that’s like saying «we are at peace» while pointing a gun at each other. The threat to use nuclear weapons is itself violence, and peace is built not by imposition but by creating opportunities for cooperation. Nuclear peace is a contradiction in itself.

Why do you think previous attempts at disarmament have failed?

When the Cold War ended, everyone thought it was the end of the nuclear threat. But countries did not disarm, because having such weapons implied having a privilege. The atomic bomb had become the currency of power, and those who had it would not give it up easily. Gorbachev and Reagan were willing to get rid of their entire arsenals, but this didn’t happen and in the end only bilateral treaties went ahead to reduce the risk, but not to eliminate it.

How does your campaign coexist with speeches promoting the use of nuclear energy as a response to the climate crisis?

Politically, they’re very different issues because one is a threat to existence itself, and the other is not. However, nuclear energy also carries a very high risk, as we’ve seen with the war in Ukraine. The Russian-occupied Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station has six reactors. A disaster there would be catastrophic for the whole of Europe and the world because it’s a global grain reserve. On the other hand, nuclear power is expensive compared to renewables and is not really green, because uranium mining is incredibly polluting.

You often say that nuclear weapons are based on a colonial and patriarchal system. What do you mean by that?

There is a xenophobic component to this kind of weaponry, the possibility of destroying a population that’s not like us, that’s different. Throughout history there have been 2,057 nuclear tests in places like the Marshall Islands, Kazakhstan and Australia, and the common denominator of the populations affected is that they were not white and not rich. On the other hand, there’s the idea of protecting though force, which is quite patriarchal. Disarmament is seen as something weak, something effeminate. In that sense, nuclear weapons are the epitome of toxic masculinity.