You are reading:

You are reading:

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent tumours in the world. One in eight women will experience breast cancer in her lifetime. Biological understanding of the breast tumour provides insights into how it will behave in the future, depending on its type or subtype. This, along with advances in immunotherapy for the most aggressive form of breast cancer, triple negative, and in the understanding of metastasis, is currently shaping the future approaches to treating this disease.

Mortality from breast cancer has decreased considerably in recent years, thanks to early diagnosis and improved treatments. In fact, according to data from the Grupo Español de Investigación en Cáncer de Mama (GEICAM), the overall survival rate is currently 85%. But breast cancer remains one of the most frequently detected tumours in the world and, in Spain, the most common among women. Hence the importance of clinical and translational research to improve the survival of patients suffering from this disease.

As Dr Eva González Suárez, researcher at the Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO), explains: “The treatment of breast cancer has undergone drastic changes in recent years. It’s probably the tumour where most advances have been made, thanks to all the research and investment in knowledge that has been carried out. In recent years, we’ve seen fundamental changes in how it’s approached, because we now have a much better understanding of the disease. In addition, we know that breast cancer is not a single disease, but that there are actually many different diseases, each with its own specific set of characteristics.”

Advances in our knowledge of the biology of this type of cancer have made it possible to have increasingly precise options that have led to an improved prognosis for patients. From diagnosis to treatment and subsequent monitoring of the disease, innovation has played a fundamental role in understanding how the disease evolves, and in offering the most appropriate option at each stage. “Knowing how the tumour will behave in the future, depending on its type or subtype, is currently marking the line to follow in the treatment of this disease,” says this expert.

Research efforts in recent years have included significant advances towards a better understanding of the molecular basis of metastasis. This occurs when cancer cells break away from the original tumour in the breast and colonise other parts of the body. It is the leading cause of mortality in breast cancer patients. Toni Celià-Terrassa, doctor in biomedicine and oncology researcher at the Hospital del Mar Research Institute, whose project has received several grants from the CaixaResearch calls, considers that one of the main challenges today is “to fully understand the immunology of metastasis, not only of the tumour in the site where it appears, which is the breast, but also when these cells spread to other organs; to understand that each organ has immune system and, therefore, the way in which breast cancer avoids interaction with the immune system in order to develop specific therapies for metastasis.”

A study in this field, led by the laboratory of researcher Roger Gomis at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) and funded by the CaixaResearch Health call, has revealed the mechanism by which the MAF protein increases the risk of metastasis in breast cancer patients. This enzyme interacts with the oestrogen receptor, altering its function and favouring the spread of the disease. The significance of this finding is enormous because the MAF protein is key to the origin of metastasis and could potentially be deactivated pharmacologically.

It should be noted that nowadays, in cases where the tumour remains localised in the breast, survival rates are remarkably high at around 85%. However, for patients whose tumour spreads beyond the breast tissue and forms metastases, the prognosis worsens dramatically.

“Metastasis does not follow a random pattern,” says Dr Gomis. “Especially in hormone-dependent breast cancer, metastasis spreads first to the bone, which already suggests that there’s some information in the tumour cell that directs it to the bone.” Previous research has already linked the MAF protein to resistance to bisphosphonate treatment, used to prevent breast cancer metastasis to bone. As Dr Gomis says, “This discovery represents a critical step towards an understanding of how breast cancer spreads, which makes it possible to prevent the metastasis process and opens up new therapeutic opportunities for patients who cannot benefit from preventive treatment to stop the spread to the bones.”

Furthermore, this research has led to development of the MAF Test, a predictive tool for patients suffering from the disease. “This diagnostic test makes it possible to identify patients with a higher risk of developing bone metastasis and helps oncologists make informed decisions about the most appropriate treatment in each case,” explains the researcher.

Immunotherapy is one of the treatments with the greatest potential for eradicating tumours. It is a therapeutic approach that consists of stimulating the patient’s own immune system to better fight malignant cells. So far, in breast cancer it is only approved as a treatment for the most aggressive cancer, triple negative. Making immunotherapy work would open a significant therapeutic door for the other subtypes of breast cancer and would become a very good option in the most advanced and metastatic cases.

It should be remembered that metastatic breast cancer, despite significant and continuing advances, is still not curable in the majority of patients. “Today, immunotherapy in breast cancer, when combined with chemotherapy, has shown a response rate compared to chemotherapy alone of 15% in the best of cases, and a prolongation of survival by a few months in advanced patients (metastatic disease). So it’s an advance but a very modest one, far from the desired outcome in clinical practice and health need. Therefore, we must better understand the biology of metastasis to find out why we do not have better responses in patients with metastasis, in order to design better strategies based on immunotherapy,” says Dr Celià-Terrassa.

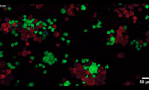

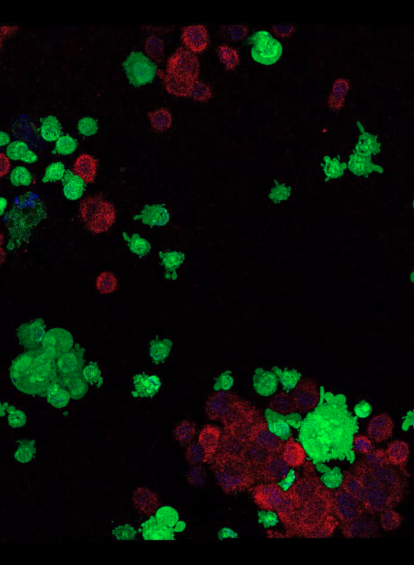

This researcher and his team have developed a new nanotherapy based on messenger RNA that, when combined with immunotherapy, activates the body’s immune system and facilitates the recognition of antigens present on tumour cells, making them visible and vulnerable. This allows the immune system to recognise and destroy them.

As Dr Celià-Terrassa explains, in this project awarded by the CaixaImpulse call, “Theyhave observed that despite treatment with immunotherapy, some cells survive and have the ability to develop resistance, a fact linked to their ability to hide from the immune system, allowing them to evade immunotherapy. We saw that this situation was reversed when the LCoR gene was activated in these types of cells and the machinery was set in motion for them to be detected by the immune system.” Furthermore, this therapy could replace chemotherapy that is combined with immunotherapy.

So far, the efficacy of this therapy has been validated in preclinical studies. “The objective now is to complete all the necessary steps to conduct the first clinical trial in humans, for which in this phase the project will focus on validating the safety of the new treatment in preclinical models. This could be brought into clinical practice, if all the steps are efficiently completed, in about six or seven years,” Celià-Terrassa points out.

In order to improve the efficacy of current immunotherapy in breast cancer, a team at the Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO) led by Dr Eva González Suárez is working on generating therapies to modulate the functionality of myeloid cells, cells of the immune system that control the anti-tumour immune response. “In the laboratory, we’ve discovered that by manipulating the RANK protein we can modify the behaviour of myeloid cells, and we want to understand how to do this in an optimal way to target breast cancer,” explains this researcher.

The RANK protein plays a key role in the development of breast tumours. This protein, which is located on the membrane of cells, sends signals that stimulate the development of the mammary gland when it binds to its partner RANKL. Malfunction of these proteins leads to the uncontrolled multiplication of these cells and, consequently, to breast cancer.

“Our results show that the RANK protein is expressed in various types of breast cancer, both hormone-positive and triple-negative. However, it’s not only the expression of the protein that is important, but also the activation of its signalling pathway, so this is where we are focusing our efforts. For example, we’ve seen that RANK seems to be more active or to have a more key functional role in menopausal women, in whom higher protein expression is associated with lower survival rates,” she clarifies.

The aim of this research, supported by the CaixaResearch Health call, is to develop treatments that attack not only tumour cells but also their environment, including myeloid cells. Existing drugs against RANK, used in the treatment of osteoporosis since 2010, could have an effect on the primary tumour, but also on metastases. “The results from our laboratory demonstrate that anti-RANK drugs prevent breast cancer in groups of women at high risk of developing it, but it’s also important to determine whether these drugs can be curative once the tumour has already developed,” says Dr González.

The project offers the possibility that RANK could become a new immune target in all tumours with a myeloid component (myeloid cells are immune cells that regulate the immune response). “One of the challenges of this work is to identify those patients who may benefit from treatments directed against the RANK pathway. On the other hand, we need to generate solid results, both in animal models and in the patient cohort, to support further clinical trials necessary for approval of the drug as an immunomodulator,” she says.

The CaixaResearch calls also support research projects aimed at better detection of the disease. One example is the project led by researchers Ana Vivancos and Cristina Saura, from the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), which focuses on detecting through breast milk breast cancer that occurs during pregnancy and the postpartum period. This type of tumour is usually diagnosed in advanced stages, which worsens its prognosis.

Breast milk from breast cancer patients is known to contain tumour cell-derived DNA (or ctDNA). Tests conducted so far show that tumour variants are found in DNA isolated from breast milk in up to 78% of cases.

Based on this discovery, the VHIO researchers are working on a clinical trial involving more than 5,000 women to test the suitability of using liquid biopsy in breast milk as a diagnostic test and to include it in routine clinical practice for earlier detection of the disease.