You are reading:

You are reading:

10.04.25

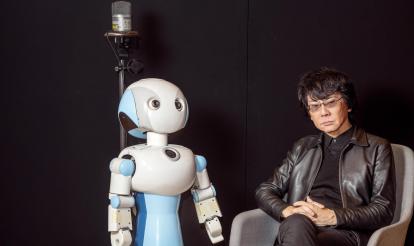

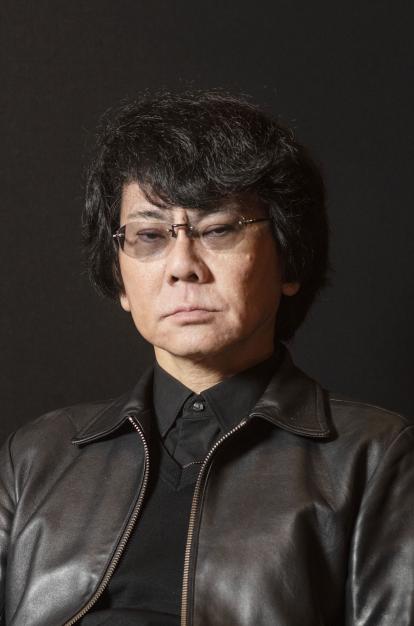

6 minutes readFamous for creating androids that replicate human beings, Hiroshi Ishiguro (Shiga, Japan, 1963) is one of the living geniuses of robotics. After 25 years of researching how we interact with machines, he now envisions a society where avatars – representations of real people – will coexist in perfect harmony with humanity.

True to his signature black attire, Hiroshi Ishiguro greets the audience attending his lecture, “Avatars and our future society”, at the CosmoCaixa Science Museum as part of the Grandes de la ciencia (Great minds of Science) series. He proceeds to share an unconventional vision of the future. “We can build a new world,” he declares, “a ‘virtualised real world’ in which diversity and inclusion can be guaranteed, and where there will be no discrimination based on the body.”

He refers to an ideal of society that he has been working on in recent years and which, far from being considered utopian, he believes will become a reality in the medium term. This vision revolves around the use of so-called avatars, representations of real people that allow interaction with others at a distance, in places where those people are not physically present.

In the world Ishiguro envisions, avatars would be robots controlled remotely in real time. However, since it is still challenging to produce and integrate autonomous androids into our societies, the Japanese scientist is focusing on virtual avatars, created by computer and interacted with through screens.

Ishiguro argues that avatars, whether in physical or digital form, could have a significant impact on improving society by revolutionising the way we interact and helping to address major social challenges.

“In Japan, we have an ageing population problem; soon, we won’t have enough people in the workforce,” he laments. “We can use avatars so that older adults, people with disabilities or those who have to stay at home to care for others can work, thereby increasing the active workforce.”

As an example, he mentions insurance companies that already use computer-generated characters as sales agents, or shops that implement them to assist customers with self-checkout counters. To demonstrate their effectiveness, Ishiguro shares the results of one of his experiments, in which an on-screen avatar was the sixth-best salesperson in a shop with 21 employees, despite not being able to move physically around the premises.

In his vision, these creations could also address medical challenges: “During the COVID-19 pandemic, we avoided going to hospitals for fear of infection,” he recalls. “Using avatars, we could have doctors and specialists visiting and treating patients who find it difficult to travel or who live in remote locations.”

Another potential application imagined by the Japanese scientist relates to education. “In today’s schools, a teacher delivers the same content to students at the same pace,” something he finds demotivating. “Every student has their own preferences and abilities, and since it’s impossible for everyone to have a private tutor, we could use avatars to encourage personalised learning.”

Hiroshi Ishiguro’s current work is part of the Moonshot Research and Development Program, a project funded by the Japanese government that aims to find solutions to complex social problems, with a view to solving them by 2050. If he succeeds in developing the “human-avatar symbiotic society” he proposes, Ishiguro will have culminated the branch of research he himself pioneered: the study of interaction between humans and robots, for which he has designed dozens of androids.

With a doctorate in systems engineering from Osaka University in 1991, Ishiguro is the director of the university’s Intelligent Robotics Laboratory. Since around 2000, he has developed various types of robots, which he has grouped under generic names such as Robovie, Repliee and Telenoid.

The most media-friendly of his creations are those in the Geminoid range, highly realistic replicas of real people, one of which represents Ishiguro himself. “We’re managing to make some of our androids move in ways that are very similar to humans,” he explains enthusiastically. After showing a video of his double speaking to the camera, he marvels, “It moves better than I do! When I speak, I can’t gesticulate with such nuanced movements.”

Ishiguro is also perfecting his creations thanks to recent advances in artificial intelligence, which have marked a qualitative leap in the discipline. “My Geminoid has improved greatly thanks to large language models,” he says. “We’ve uploaded all my books and interviews into my replica, and my students have designed a personality for it similar to mine. Now it can teach and give lectures in my place, in more languages than me and with better pronunciation,” he jokes.

Despite having spent years working to create exact replicas of human beings, Ishiguro believes it is difficult to evaluate the results impartially. “People say my robot looks a lot like me, but I don’t think so. When I look in the mirror, I see an inverted image of myself, but the Geminoid isn’t reversed. I don’t think I can make objective observations about myself.”

Ishiguro argues that these kinds of observations, rather than technical ones, underpin the task of creating a robot. “The key to designing androids is asking fundamental questions, like: What does it mean to be human? That’s the main question.”

A good example of these questions is his effort to recreate what the Japanese call sonzaikan, a term that refers to the feeling of being in someone’s presence. “When we close our eyes, we can sense if someone is nearby,” Ishiguro explains. “But how can we develop an avatar that has sonzaikan, that conveys a human-like presence? That’s something we haven’t figured out yet.”

Even more complicated is the challenge of endowing androids with will, something the scientist considers essential. “If we want to have autonomous robots, we need to design their desires, but we must be careful to ensure they are not harmful,” he warns. “We need to engage in discussions with philosophers, cognitive scientists and researchers from other fields,” as he acknowledges that some aspects of this technology touch on humanistic disciplines and are yet to be defined.

“I believe society evolves, and it’s good for ideals to evolve too,” responds Ishiguro to a question from the audience at CosmoCaixa which doubts whether people will ever allow the creation of their doubles. “These creations should not be seen as substitutes for human beings, but as tools that expand our capabilities. To achieve a human-avatar symbiotic society, we must change technology, but also the way society thinks.”

Ishiguro concludes his talk in the Grandes de la ciencia series with optimism about the future, though he acknowledges that no-one truly knows what tomorrow holds: “It may be that, through our research, those of us working on engineering, creation and scientific projects are contributing to the evolution of ethics and society,” he says with hope. “As creators, we must think about what’s best for society, what a better tomorrow would look like. We must continue to work on the multitude of possible scenarios, while at the same time avoiding dangerous situations; that is our challenge.”