You are reading:

You are reading:

Master of the sequence shot, irony and satire, Berlanga is one of the greatest directors in the history of Spanish cinema and the one who best portrayed the society and problems of an era. With the help of his son José Luis and in the context of the exhibition Interior Berlanga, which opens at CaixaForum València on 29 February, we retrace the life of this author, who created his own language and universe, Berlanguian, and left us such titles as Plácido and El verdugo.

It was Georg Wilhelm Pabst’s Don Quichotte that awakened his vocation for cinema. Highly inquisitive and a keen observer, probably due to his shyness, Luis García-Berlanga always liked working behind the camera because, he said, it was the closest thing he knew to being God. Rigorous and perfectionist down to the smallest detail, he was an enthusiast of the sequence shot and brought order and a sense of humour where everything seemed chaotic and dramatic. He was also in the habit of repeating scenes until the last minute of filming was used up, even if it had gone well the first time. “Just in case,” he thought.

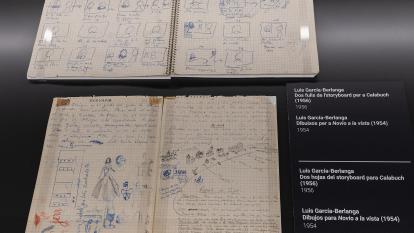

“Just in case”, he also kept absolutely everything in the studio where he worked: letters, notebooks, poems, scripts, photographs, plastic packaging, shoelaces and empty medicine bottles with rubber stoppers. Part of this material, stored in more than 70 boxes that today form part of his personal archive at the Filmoteca Española (Spanish Film Archive), has been catalogued and digitised thanks to the support of the ”la Caixa” Foundation, and the public can discover it from 1 March to 9 June in the Interior Berlanga exhibition at CaixaForum València. “It’s called the Diogenes syndrome,” says his son, José Luis García-Berlanga. “He wasn’t vain, I don’t think he did it for posterity’s sake, but because he thought everything might be useful at some given moment.”

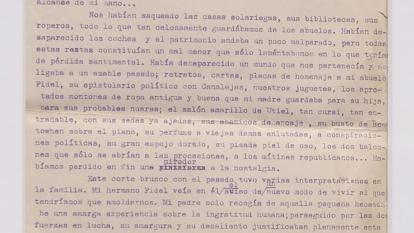

Born in Valencia in 1921, Luis García-Berlanga came from a bourgeois family of landowners and merchants who had been involved in Spanish politics: his grandfather had been a member of the Liberal Party of Sagasta, and his father, of the Radical Republican Party and the Republican Union. From those early years of his youth, “among all the writings, there’s one that particularly moved us, which is a letter he wrote just at the end of the Civil War, in April 1939,” explains the exhibition curator, Bernardo Sánchez Salas. “A personal summary, typed, in which he reflected upon the effects of the war on himself, his family and Spanish society. It’s one sheet of paper. I’ve never read anything like it. It’s an absolutely extraordinary document.”

Shortly afterwards, at the age of 20, Berlanga joined the Blue Division, where he never fired a single shot. From his time there, the filmmaker kept some belongings that now form part of Interior Berlanga: insignia, medals, letters, smoking tobacco and even the cutlery he used to eat with during the years he lived abroad. “He talked very little about that time,” recalls his son. “He’d enlisted for a number of reasons. My grandfather had been sentenced to death because he’d been a Republican Member of Parliament, and someone suggested it would help if his sons joined the Blue Division. On the other hand, he himself sympathised and flirted with a group of Falangist people. But above all, he explained when he was older, he did it to impress a girl who wasn’t paying any attention to him. When he returned, she was already married.”

Like just another of his characters, Berlanga was left without the girl, but he returned from the war with clearer ideas. “My father was a bourgeois gentleman with an anarchist philosophy. He came back from Russia very mentally free of ideologies and religious beliefs. That allowed him to always be everywhere and nowhere. His freedom was something he never negotiated and which was tolerated with more or less criticism.”

On his return, the filmmaker enrolled in law school and attended the València School of Philosophy and Literature, before joining the Institute of Cinematographic Research and Experimentation (IIEC) in Madrid. His creative interests had always been there, as evidenced by the poetry notebooks and youth and childhood diaries on display in the exhibition. Even as a teenager, he had wanted to be a painter and wrote poetry. He even submitted work to the Adonáis Poetry Prize. “He always said that he had an epiphany when he saw Pabst’s Don Quichotte, which was a far cry from his films. I don’t know if that’s true. The truth is that he’d signed up for some of those courses to be able to play in the football team, he used to run the 400 metres at the time and was very sporty, but he was already beginning to feel the need to tell stories and he saw cinema as a means of doing that,” says his son.

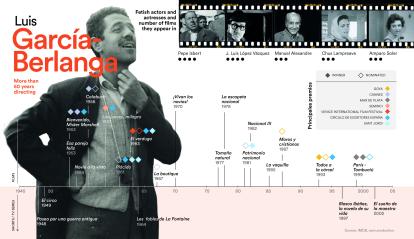

It was precisely at the Official School of Cinematography – formerly the IIEC – that Berlanga met Juan Antonio Bardem. Together they made their debut in 1951 with Esa pareja feliz, starring Fernando Fernán Gómez and Elvira Quintillá, followed by one of the most famous titles in his filmography, Bienvenido, Mister Marshall (1953), a scathing critique of the society and politics of the time, with José Isbert, Manolo Morán and Lolita Sevilla as the lead actors. Berlanga then began the curious tradition of using Austro-Hungarian as a fetish word in each of his films.

Nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1961 for Plácido, his films were characterised by the use of sharp irony and an exquisite sense of humour to tell the story of social dramas. “Berlanga was a genius,” admits his son. “His character went beyond and transcended the mere presence of the filmmaker. He had his own language, a syntax and a Berlanguian cinematographic narrative that people try to imitate, but can’t pull it off. A story like El verdugo, which speaks about the loneliness of an individual in the face of society, who in the end has to kill another against his own nature in order to get a subsidised flat, is something that is part of universal culture.”

As well as being a faithful reflection of the reality of the time, the director proved to be a great observer. “He also had great curiosity and imagination. He was not a filmmaker who told what he’d seen. He never lived in a village, but the one in Bienvenido, Mister Marshall is a village you believe in, and the same goes for the one in Calabuch.” His stories still speak to us of the past and the present. “What evolves is the surroundings. Berlanga’s costumbrismo reflects the society in which he was born. It’s only the background of the canvas to tell stories that are universal. The story of an individual or a group that tries something and always ends up failing. That’s why his films are still relevant.”

However, it is impossible to understand the director’s work without talking about the tandem he formed with screenwriter Rafael Azcona, with whom he worked on some of his most brilliant films – the “Trilogía nacional”, La vaquilla, El verdugo, Plácido. They met in 1959 on their first assignment together, Se vende un tranvía, and their good rapport and friendship lasted until 1987, when it was broken off for good. The reason was never known. “Azcona was the most brilliant, the funniest and the best conversationalist I ever met,” says García-Berlanga Jr. “He had a lot of charisma. After his divorce from my father, when they weren’t speaking to each other, I continued seeing him.”

In fact, the script was everything to Berlanga. So much so that he even sent his own proposal to Charles Chaplin, a proposal the actor rejected because he did not work with other people’s scripts, according to a letter that the filmmaker kept with the rest of his things, such as the first script for his films La Escopeta Nacional and Patrimonio Nacional, as well as other scripts that he never realised and which are now on display at the CaixaForum València exhibition. Also fundamental was his work with actors, with whom he had a reputation for giving few indications. Actors such as Luis Cigés, Manuel Alexandre and Agustín González became unconditional fans of his films. “His casts were made up of fixed actors and characters,” says Sol Carnicero, curator of the exhibition with Sánchez Salas and production director of many of the director’s works. “When he liked someone, he fell in love with that actor. We have the irreplaceable José Luis López Vázquez, Amparo Soler Leal or Chus Lampreave, who was a Berlanga girl before she was an Almodóvar girl. And yes, there were people that Berlanga always wanted to have in his casts. In fact, when I started working with him he almost always asked me about actors who had died and wanted me to confirm that they weren’t really alive, because he thought that maybe they were in an old people’s home.”

A master of filming sequence shots and controlling chaos, he always paid particular attention to the choreography of the actors and the mise-en-scène. Some of the storyboards of projects such as Bienvenido, Mister Marshall or Calabuch, a film of which he even kept several pages of the first sequence, or the shots of the sets of such titles as Esa pareja feliz or Todos a la cárcel, exhibited at CaixaForum València, speak of how the filmmaker left nothing out of control. “He said that, since he was very lazy, that way he saved on editing and did everything in one take. In reality, one of his sequence shots took two days to shoot,” says his son. “It’s a perfect choreography of actors, camera, light and sound, and he managed to make the work go unnoticed.”

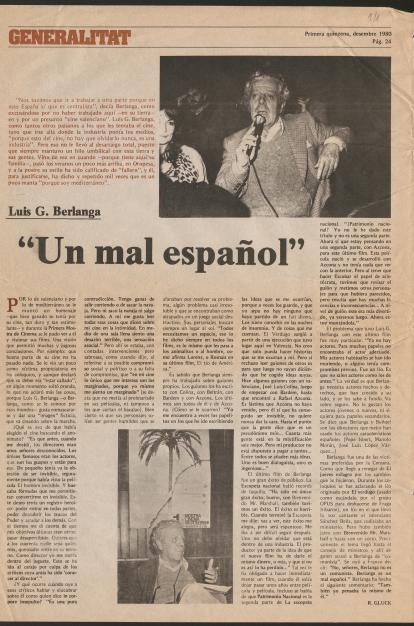

The outcome of his stories was so natural that Berlanga also became an expert at outwitting Franco’s censors. “The creators of the time had grown up with censorship. They always put out bait that they knew would be taken out, to divert attention. But they weren’t obsessed with it, partly because they had a very good idea of what they could do and where they could go. They were also less politically aware than the generation that followed Saura. They just wanted to tell their story. My father was often criticised at the beginning for not making committed cinema. But there’s no more social cinema than Plácido.” In fact, there was no cinema more critical than Berlanga’s, as Franco himself stated when, after watching El Verdugo for the first time, he said: “Berlanga is not a communist, he is something much worse than that, he is a bad Spaniard.”

Berlanga, who married María Jesús Manrique de Aragón in 1954, had four sons during his lifetime: José Luis, Jorge, Carlos and Fernando. Two of them, Jorge and Carlos, sadly died of liver disease at the ages of 52 and 42 respectively. In his family circle, the filmmaker was “a father and a bourgeois husband, who often complained to his wife about everything. He was a little lord who had always been spoiled by my grandmother,” says his son José Luis. The house where the eldest of his sons – now a television producer, hotelier and chef – and his siblings grew up was visited by diverse personalities, including Mario Vargas Llosa, Tono and Mihura, Rafael Azcona and Mingote. “They were very brilliant people. But the day-to-day life was the usual of a bourgeois house, with the usual worries. In summer we used to go rock mussel picking with snorkelling gear and a knife. It was our great passion. Then in the afternoon, after the siesta, my brother Carlos and my father would have a quick painting competition. Carlos was a great illustrator and a great painter, my father loved it,” he recalls, “and sometimes one would start and the other would finish. But there were no differences. It was a normal life for me.”

National Film Award (1980), Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts (1981), Prince of Asturias Award (1986) and Goya for Best Director in 1993 for Todos a la cárcel, whose statuette will also travel to the exhibition, as well as his Oscar nomination in 1961 for Plácido – from which ceremony he kept the programme, a pair of tickets and a pass. Berlanga received recognition at the most important international festivals, such as Cannes, Venice, Montreal and Berlin. He was a close friend of René Clair, with whom he posed for photographs and even corresponded, and of Federico Fellini, whom he knew because they had both worked with the screenwriter Ennio Flaiano. In one of his boxes there was also the award of the Key to the City of Miami. According to his son, “Bienvenido, Mister Marshall triumphed because it was a breath of fresh air. El verdugo had a huge impact from the United States to Colombia. In Russia, he was on the jury of the Moscow Festival a couple of times. There’s a legend that says his films are very difficult to watch outside [of Spain] because his characters all speak at the same time. But when you see a sequence shot of Plácido, in which it seems most like everyone is talking all at once, no actor ever speaks over the other.”

A fierce perfectionist, Berlanga always felt close to his most unsuccessful characters. “He was never satisfied with anything he did,” continues José Luis García-Berlanga. “He would eat up every day until the end. ‘I’m sure there’s room for improvement,’ he would say. He complained a lot about the endings of his films, even though they were great. The one that stuck in his heart the most was the ending of Los jueves, milagro. We know that the censors changed it and that Jorge Grao finished it, but we’ve never managed to find out exactly what they modified. He even asked not to sign off the film. In the Filmoteca Española archive there are loads of letters he wrote to his academic friends who were pro-Franco, in which he pointed out that it was unacceptable.”

Be that as it may, his way of seeing and living reality transcended his cinematic universe to such an extent that the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) even included the word berlanguiano (Berlanguian) in its dictionary. “There’s no rule for something to be berlanguiano,” says his son. “What it does have is a virtue, that you see something and immediately recognise it as such.”

Although it was a mission impossible for Sol Carnicero, in the exhibition they have tried to explain it. “In fact, there’s a space in which some people try to define it, and we’ve never reached an agreement. For me, it’s something that seems absurd, that is completely incomprehensible, but at the same time is real. And then we realise that the incomprehensible and the absurd is what we’re living every day.”

Berlanga made his last film, Paris-Tombouctou, in 1999. In 2008, he deposited in the Caja de las Letras at the Instituto Cervantes the unpublished text of ¡Viva Rusia!, the project for the fourth film in the Leguineche family saga that he had written with his son Jorge, Rafael Azcona and Manuel Hidalgo. The hidden contents of that box, of which a reading performance will be made as an exclusive at CaixaForum València, were revealed with great anticipation on the filmmaker’s centenary in June 2021. Berlanga had been dead for more than a decade: he had passed away on 13 November 2010, at the age of 89.

After his death, we are left with his universe. An inspiring and timeless cinema, capable of reopening current debates with titles like Tamaño natural, in which he posed the love of a lonely man for a life-size doll, today perhaps a product of artificial intelligence; the problem of rent in El verdugo or the difficulties of making ends meet in Plácido. “And they weren’t happy nor did they live happily ever after”, as the director would say in La escopeta nacional, displaying that eternal semi-dramatic smile that his work has left us with. At least we will always have his films.