You are reading:

You are reading:

The exhibition Top Secret. Cinema and Espionage at CaixaForum Barcelona, organised with the Cinémathèque Française, traces the figure of the spy from the beginning of the 20th century to the present day, breaking numerous clichés and stereotypes, including that of the double agent, to end the femme fatale by identifying her as a free, empowered and feminist woman.

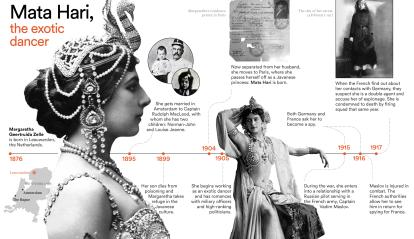

Greta Garbo, Jeanne Moreau and Sylvia Kristel made her a cinematic myth. The most famous secret agent of the First World War, the Dutchwoman Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, better known as Mata Hari, was an exotic dancer supposedly working for the Germans who came to embody like no other the idyllic prototype of the female spy: attractive and seductive, a true femme fatale capable of extracting all sorts of sensitive information from the enemy between the sheets of a bedchamber. Feared and admired, her character represented the best and the worst of the ambivalence of both worlds, the fictional and the real. On the other side of the cameras, the shots, the special effects, the music and the plot twists, was the grim reality: being sentenced to death by firing squad for treason in 1917, without trial or legal representation.

It is said that in her last moments she refused to wear a blindfold before the rain of lead. It did not matter that, according to Alexandra Midal, professor at HEAD University in Geneva and curator of the exhibition along with Matthieu Orléan, “this inveterate seductress, who could dance like no other woman of her time, was probably not a spy per se”. In fact, the few pieces of information she did divulge, some of it from the press in other countries, were of little consequence. Moreover, according to chroniclers of the time, although she was extremely charismatic, “she didn’t particularly shine as a dancer”.

The story of Margaretha, condemned to live between myth and reality – she herself invented an exotic past in the East Indies (now Indonesia) – serves to illustrate the spirit of this captivating exhibition, which shows the inevitable relationship between the seventh art and the secret services and the game of mirrors between reality and fantasy, while not forgetting the feminist interpretation. A world of simulations and disguises, surrounded by props, cameras, microphones and gadgets, whose diffuse barrier was easily permeable towards one side or the other. In fact, many of the performers ended up becoming spies.

Mata Hari is one of the most obvious examples, but as Midal warns, espionage in general does not correspond “to that image of the alpha male embodied by the figure of James Bond. There’s another completely different story that we want to show in the exhibition, a version that, from a feminist and feminine point of view, is linked to the question of women’s identity and a deconstruction of the myth”, because it seeks to distance itself from what is known in American terminology as the honeypot: undercover agents, usually female, who seduced men to achieve their objectives.

The charismatic, duplicitous female spy, that stereotype nurtured by both film and literature, had little to do with reality, but it helped to make women a real threat to national security, which in the mid-20th century spawned an entire public awareness campaign warning citizens with slogans such as: “Keep mum – she’s not so dumb! Careless talk costs lives".

“These posters,” says Midal, “reminded the soldiers that women were not to be taken for fools, but behind the main message there was also contempt for them. It said that they were better at hiding and concealing, and that they were only there for their pretty faces.” However, this image had its positive side. “In reality, this femme fatale icon allowed them to do their job: to be discreet and go unnoticed in order to achieve their goals, because no-one imagined that a spy could look like someone like you or me.”

However, there is no single prototype for a female spy. If history is any guide, there are cases such as the French aviator Marthe Richard, or Princess Yoshiko Kawashima, considered Japan’s best double agent during the Second World War. Beyond the long shadow of Mata Hari, diversity also reached the silver screen. Margaretha, for example, had nothing to do with Protéa, the heroine of the 1913 film of the same name directed by the Frenchman Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset: a passionate jiu-jitsu enthusiast and martial arts expert who holds the title of being the first woman spy in the history of the seventh art.

Many others followed. From Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious, in which a brilliant Ingrid Bergman played the fictional double agent Alicia Huberman, to Fritz Lang’s Spies, inspired by a real-life event in the early 20th century – the suspicion that the Arcos co-operative society was hiding a secret Communist office. It introduced the character of Sonya Baranilkova (played by Gerda Maurus), whose mission was to seduce and counteract the state police agent investigating the society. Interestingly, in the late 1930s, the German Ursula Kuczynski, mother of a family and the best Soviet spy of the time, would pay homage to this character by adopting the codename Sonya or Sonja to carry out her most dangerous missions.

There have also been great actresses who were spies, a natural progression by all accounts. “Both professions,” the curator reflects, “start from the same place: they have to play a character and be credible. Moreover, “their travels to make films, boost morale among the troops, sing or dance could be accompanied by the exchange of documents and information,” she explains. Performers like Groucho Marx, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Joséphine Baker, who was able to use her musical scores to convey sensitive information, took advantage of these conditions. “We also know that TV chef Julia Child, whose story was brought to the big screen by Meryl Streep, was a spy during the Second World War,” the expert recalls. “Actresses were an excellent way for a country to carry out successful espionage.”

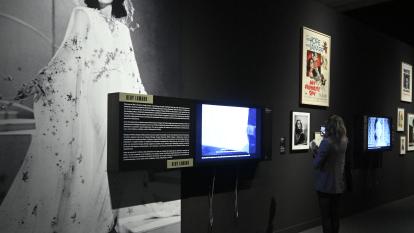

But perhaps, she insists, the star who contributed most to the development of espionage was Hedy Lamarr. Considered the most beautiful woman in the universe, the actress began her film career in scandalous fashion when she simulated the first orgasm in screen history in Ecstasy (1933). “What a scandal!” exclaims Midal ironically. “Her parents locked her in her room at the age of 18 and only let her out to marry an arms industry magnate,” she says. “It was precisely in his factory that she learned to be a great inventor.” Self-taught and fascinated by technology, she devised a system that prevented torpedoes from being intercepted or hacked by enemy forces. “Also,” she adds, “what she invented in the 1940s gave us Wi-Fi and mobile phones today. So, in reality, she was an actress who appeared in spy movies – The Conspirators (1944) or My Favourite Spy (1951) – but at the same time invented things that changed the world.”

According to Midal, the challenge of the exhibition, which is divided into five sections – technology, the two world wars, the post-war period, terrorism, and modern espionage – is “to show how cinema takes on what we could say is the oldest vocation in the world and, at the same time, that espionage is a very current profession, as the tense situations we live in today show”. Furthermore, the display, which began at CaixaForum Madrid, will be in Barcelona until 17 March and will then travel to Zaragoza, Seville and Valencia, “also aims to demonstrate how fiction and reality intermingle”. Film posters and scenes, gadgets and costumes, as well as the bust of Arnold Schwarzenegger from Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall, are mixed with X-ray records used to evade Soviet censorship, sophisticated weapons and poisons, unexpected microphones and the latest recording technologies.

“There are constant comings and goings between film and espionage, as explains Jonna Mendez, the CIA’s Chief of Disguise, who often turned to film to do her job. In the same way, we see that cinema draws inspiration from what goes on in the secret services,” says Midal. They both interact with and feed off each other. “In this respect, the exhibition also addresses the question of image and sound capture. We see that recording technologies, which are indispensable in film, are constantly shaping the world of espionage to enable discreet listening or viewing from a distance.”

Between the 20th and 21st centuries, however, there was a real paradigm shift in how the spy was portrayed. Until then, the double agent worked for the government or an institution. “There’s something very patriotic about the profession. But little by little a change occurs, not only when the Berlin Wall falls, but also when there’s no longer any opposition between the two blocs,” explains the curator. “This kind of spy, like in the case of Carrie Mathison in Homeland, is faced with an unprecedented situation in which she can no longer trust the authorities, she has only herself.” Claire Danes’ character “speaks volumes about modern espionage and the current geopolitical situation. Homeland is the first series in which we really go to the Middle East and begin to come out of this battle between the Eastern and Western blocs.”

The prototype has changed. Carrie is an incredibly free, brave and clever woman. “For her, her beliefs are more important than anything else, and that’s hugely important because it’s what we’re going to find in contemporary espionage. I’m talking about so-called whistleblowers. They’re not individuals trained by the secret services, nor do they obey a particular government, rather they follow ideals.”

Such is the case of Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning, who is the subject of an installation at the end of the exhibition: “She’s someone who works in the army, for the government, and who discovers such momentous facts that she decides, as a citizen, to make them public. In her autobiography, she recounts that when she started releasing these documents, she didn’t think she was taking any risks because no-one had ever done it before.” Manning was sentenced to 35 years in prison, but was released early and is now a free woman.

Her example serves the curator to illustrate that today, in reality, a spy can be any normal person. “Just like you or me, if we had access to certain information that went against our morals or principles and decided to make it public, bypassing hierarchies and the administrative system. This view of that kind of espionage is incredibly contemporary and, personally,” she concludes, “I find it wonderful and hopeful.”