CaixaForum Madrid is hosting an exhibition devoted to Henri Matisse (1869–1954), featuring works from all periods of his career, shown in dialogue with major figures of 20th-century art and a selection of contemporary artists who pay tribute to him. The result of a collaboration between Centre Pompidou and the ”la Caixa” Foundation, the show brings together 46 works by Matisse and 49 by other artists, creating a web of cross-references that sheds light on a century of creativity and avant-garde expression.

The director of CaixaForum Madrid, Isabel Fuentes, and the Chief Curator of Modern Collections, Musée national d’art moderne – Centre Pompidou, Aurélie Verdier, have presented the exhibition Chez Matisse: The Legacy of a New Approach to Painting.

![August Macke, Lautenspielerin [Woman Playing the Lute], 1910. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 4348 P.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_414_626/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1b8ac0b7.jpeg)

The exhibition devoted to Matisse is the first under the second major strategic partnership renewed between the ”la Caixa” Foundation and Centre Pompidou in Paris to jointly organise exhibitions. It will be on display at CaixaForum Madrid from 28 October 2025 to 22 February 2026, before travelling to CaixaForum Barcelona, where it will run from 26 March to 16 August 2026.

Around 1900, Matisse’s work revolutionised European painting with a bold and explosive new vision of colour. In the 1950s, his collages transformed the very concept of pictorial space. Between these two pivotal moments unfolded more than fifty years of artistic exploration that made Matisse’s work the very home of modern art, visited by artists of many generations and movements. Hence the title Chez Matisse, which highlights the artist’s spirit of hospitality and creative kinship.

Primitive and sophisticated, classical and wild, figurative and abstract, Henri Matisse (1869–1954) is a key figure of modernity, capable of captivating a wide-ranging audience while dazzling fellow artists, who regard him as both a reference point and a companion in artistic exploration.

![Natalia Goncharova, Nature morte au homard [Still Life with Lobster], 1909-1910. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 81-65-857.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_414_233/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1ab5875f.jpeg)

![Alexej Von Jawlensky, Byzantinerin (Helle Lippen) [Byzantine Woman (Pale Lips)], 1913. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 1982-44.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_414_233/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f18ca9723.jpeg)

Chez Matisse: The Legacy of a New Approach to Painting presents works by Pierre Bonnard, Georges Braque, Daniel Buren, Robert Delaunay, André Derain, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, František Kupka, Mijaíl F. Lariónov, Le Corbusier, Jacques Lipchitz, Albert Marquet, Barnett Newman, Emil Nolde, Picasso, Kees van Dongen and Maurice de Vlaminck, among others.

One of the intriguing aspects of the exhibition is the introduction of a female perspective through the work of Sonia Delaunay, Françoise Gilot, Natalia Goncharova, Baya [Fatma Haddad], Anna-Eva Bergman and Zoulikha Bouabdellah, who explore themes of decorative art, the boundaries of painting, and the place of the feminine.

Why does Matisse hold a place in the pantheon of modern art history? Because of his understanding of the most innovative artists of the 19th century and his ability to create new visual languages for his own time. Born into a family of weavers and pigment merchants, Matisse’s work is the result of tireless dedication, enabling him to achieve a complex mastery of simplicity.

His innovative conception of colour and his critical rethinking of the canvas as a pictorial surface quickly resonated with the German Fauves, the Russian Neo-Primitivists and American painting of the 1940s. His work mirrors his era, from the anguish and introspection of the war years to the explosion of sensuality and hedonism in his later paintings and collages.

Eight sections trace Matisse’s artistic journey in chronological order

The exhibition is divided into eight sections, arranged chronologically, which unfold Matisse’s work and highlight his influence on artists of the 20th and 21st centuries.

- Line and colour (1900-1906)

![Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret), Métamorphose du violon [Metamorphosis of a Violin], 1920-1952. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 3342 P.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_414_626/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1782d2a5.jpeg)

A self-portrait, a Parisian landscape, and two calm, shadowy still lifes painted between 1900 and 1902 bear witness to the early stages of Matisse’s career, shaped by the influence of his teacher Gustave Moreau. Pleasure, Peace and Opulence (1904), signals a turning point, with a pictorial approach based on the fragmentation of light and the harmony between subject – a seaside lunch – and the beauty of form.

In dialogue with the landscapes of Saint-Tropez and Collioure, Matisse’s palette becomes incandescent. Albert Marquet, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Georges Braque, and Robert and Sonia Delaunay all take part in the same revolution.

- Primitivisms or emotions (1907-1913)

The discovery of non-Western art and primitivism allowed Matisse to challenge the established canon. This section presents his sculptures from 1907 to 1930, displayed alongside L’Enlèvement d’Europe [The Rape of Europa], a 1938 work by Jacques Lipchitz. Matisse connected with the German and Russian avant-gardes, which were also drawn to so-called primitive art.

Like his German contemporaries – Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde – he sought an emotional foundation for art. In Russia, Matisse’s work was exhibited alongside paintings by Mikhail F. Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, who drew inspiration from folk imagery.

- Conjuring

apparitions (1914-1917)

During the years of the First World War, Matisse’s palette returned to darkness. He defined an intimate space and introduced the motif of the door and the window, thresholds to a disquieting world, which found an echo in the work of contemporaries like Kees Van Dongen and František Kupka. During his sittings, Matisse sought to establish an empathetic connection and capture the flow of energy between artist and model. In his portraits of the actress Greta Prozor (1916) and the collector Auguste Pellerin (1917), the human figure appears surrounded by a ghostly aura.

![Henri Matisse, Intérieur, bocal de poissons rouges [Interior with Goldfish], spring of 1914. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 4311 P © Succession H. Matisse/ VEGAP/ 2025.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_414_233/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1934dfb6.jpeg)

- Increasing abstraction (1914-1917)

During the emergence of Cubism in 1908, Matisse became a privileged witness and a meeting point for the Parisian avant-garde, welcoming leading artists of the time into his home. In August 1914, while living in Collioure, he created Porte-fenêtre à Collioure, a key work which, although unfinished, marked his first approach to the concept of “black light”, using intense chromatic planes that anticipated new directions in his painting.

This approach influenced both the formal development of František Kupka, with his compositions of vertical bands and abstract aspirations, and Matisse’s own work, exemplified in the portrait of his daughter Marguerite, where the Cubist orthogonal structure merges with an aura of stylistic mystery.

- ‘Our heart points to the south’ (1917-1929)

In late 1917, Matisse moved to Nice, on the French Riviera. He set aside the experimental dimension of his work and focused on interior scenes, featuring female models that allowed him to explore the relationship between figure and space. The figures and accessories in these works recall his travels in Spain and the Maghreb.

As with Albert Marquet and Kees Van Dongen, the Mediterranean light accelerated the renewal of his pictorial solutions. Matisse and Natalia Goncharova (who discovered Spain in 1916) both presented the archetype of the mantilla-clad woman – hieratic and decorative – as a contemporary icon.

- Classical modernities: Matisse

and his dialogue with Bonnard, Gilot and Picasso (1930-1938)

In the 1930s, Matisse travelled to the United States and Oceania. He simplified his drawing and extended it into space. This section juxtaposes Matisse’s still life Nature morte au buffet vert (1928) with Picasso’s Naturaleza muerta con candelero (1944) and Françoise Gilot’s Évier et tomates (1951) to illustrate Matisse’s influence on the artistic couple, while also highlighting their differences: Gilot shared Matisse’s empathic approach to objects, whereas Picasso asserts his own personality. In 1936, Matisse experienced a creative block and returned to Cézanne and Bonnard to resolve his dilemma of how to approach the human figure.

- Days of colour: painting

and film after 1939

From 1936 onwards, Matisse used gouache-painted papers for magazine covers. In his 1947 book Jazz, this technique achieved full autonomy. Matisse offered a solution to the longstanding conflict between line and colour: he cut directly into colour, creating forms distilled to their essence.

In 1951, he collaborated with Le Corbusier on the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, on the French Riviera. Matisse became a reference point for American abstract painters such as Barnett Newman.

In France, Raymond Hains and Jacques Villeglé sought to move beyond painting, setting Matisse in motion in their film Pénélope (1950–1980). Likewise, the compositions of the self-taught Algerian artist Baya recall the painter’s powerful decorative energy.

![Henri Matisse, Porte-fenêtre à Collioure [French Window in Collioure], September-October 1914. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 1983-508.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_414_233/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f195be3ed.jpeg)

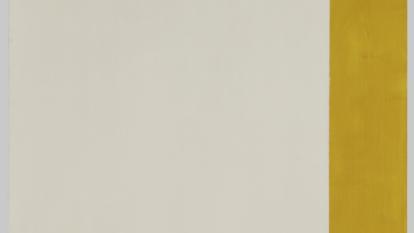

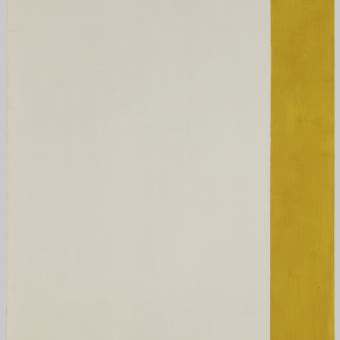

![Daniel Buren, Peinture aux formes indéfinies [Painting with Indefinite Forms], May 1966. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 1986-255.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_414_233/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1a906019.jpeg)

- ‘Chez Matisse’,

multiple horizons (1961-1970)

In 1961, the exhibition Henri Matisse: Les grandes gouaches découpées at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris brought Matisse’s work into contact with the young artists Daniel Buren and Michel Parmentier, who discovered through it the technique of collage and the importance of the white background as an active element in composition. Their conceptual approach excluded Matisse’s emotional and subjective values.

The exhibition concludes with a reflection on the role of Matisse’s work as an inspiration for the new modernity, pop art and postcolonial forms in painting, video and film. This section highlights the work of the Russian-Algerian video artist Zoulikha Bouabdellah.

The decorative

“The decorative is something extremely valuable in a work of art. It is an essential quality. It is not pejorative to say that an artist’s paintings are decorative. […] The essence of modern art is to be part of our lives. A painting in an interior radiates around it, through its colours, a joy that lightens us,” declared Matisse in an interview in 1945.

The exhibition also explores the value of the decorative through its resonance with the work of the Russian artist Natalia Goncharova. “Decorative painting? Poetic poetry. Musical music. It’s absurd. All painting is decorative, since it decorates, colours, beautifies. And as for things that are merely decorative – the truth is, I know of none,” wrote the great Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva in reference to Goncharova.

Beauty and the nude

How can we approach, from a contemporary perspective, the paintings of nude odalisques that Matisse created at different stages of his career? Matisse reflected deeply on the nude, freeing it from the yoke of beauty and imposed canons. He presented a body that is not the embodiment of beauty, but an abstract form.

In the words of the artist Zoulikha Bouabdellah, Matisse’s nudes “grant us a power we must seize, that of subjecting them to the test of our own questioning: is it not reductive to see in the depiction of the female nude merely an offering to male desire? And by refusing to look at these bodies, are we not imprisoning them a second time?”

Illness

In the final years of his life, Matisse was forced to put down his brushes. This setback, however, awakened his artistic instinct. Some of his late creations, made with painted and cut-out papers, are now considered classics of 20th-century art. Their influence extends far beyond the art world: they are iconic works, endlessly imitated and used in commercial contexts. Out of deprivation and pain, Matisse built a world full of light.

![Raymond Hains, Film abstrait [Abstract Film], 1952-1976. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 1977-619.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_414_239/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1a4a0f47.jpeg)

Mediation

The exhibition includes a mediation space that invites visitors to step into the atmosphere of an artist’s studio. In his later years, Matisse worked with cut-outs made from paper he had painted himself, which spread across the walls of his studio, often as a preparatory step for mural works.

Other artists featured in Chez Matisse: The Legacy of a New Approach to Painting have also worked on large-scale canvases or directly on the walls of their studios, where they spend many hours and which ultimately become part of their artistic practice.

This space recreates a collective studio where visitors can draw inspiration from the works of Matisse and other artists in the exhibition, such as Daniel Buren or Shirley Jaffe, to create their own compositions.

![Natalia Goncharova, Nature morte au homard [Still Life with Lobster], 1909-1910. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 81-65-857.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_340_340/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1ab5875f.jpeg)

![Alexej Von Jawlensky, Byzantinerin (Helle Lippen) [Byzantine Woman (Pale Lips)], 1913. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 1982-44.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_340_340/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f18ca9723.jpeg)

![Henri Matisse, Intérieur, bocal de poissons rouges [Interior with Goldfish], spring of 1914. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 4311 P © Succession H. Matisse/ VEGAP/ 2025.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_340_340/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1934dfb6.jpeg)

![Henri Matisse, Porte-fenêtre à Collioure [French Window in Collioure], September-October 1914. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 1983-508.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_340_340/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f195be3ed.jpeg)

![Daniel Buren, Peinture aux formes indéfinies [Painting with Indefinite Forms], May 1966. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 1986-255.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_340_340/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1a906019.jpeg)

![Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret), Métamorphose du violon [Metamorphosis of a Violin], 1920-1952. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 3342 P.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_340_340/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1782d2a5.jpeg)

![August Macke, Lautenspielerin [Woman Playing the Lute], 1910. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 4348 P.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_340_340/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1b8ac0b7.jpeg)

![Raymond Hains, Film abstrait [Abstract Film], 1952-1976. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle AM 1977-619.](https://imagenes-mediahub.fundacionlacaixa.org/files/image_340_340/uploads/2025/10/23/68f9f1a4a0f47.jpeg)