The Musée d’Art et d’Histoire (MAH) and the ”la Caixa” Foundation present The Reappearing Image, an exhibition that explores the way in which contemporary artists dialogue with the past. Specifically conceived for the MAH, The Reappearing Image brings together 18 works selected from the prestigious ”la Caixa” Foundation Contemporary Art Collection.

The exhibition, curated by the director of the Contemporary Art Collection of the ”la Caixa” Foundation, Nimfa Bisbe, and Carlos Martín, offers an unprecedented immersion into how contemporary artists face and reinterpret the tradition and history of art. How do they integrate or question these elements in their practice? The Reappearing Image, presented at the Musée Rath, brings together works whose nexus lies in the sovereignty of the image, an image that is supposedly meant to be venerated or one that should be treated with suspicion.

Introduction

From a spark ignited by a dual inspiration - a selection of works from the ”la Caixa” Foundation in a dialogue with the past and an immersion in the Musée Rath - this exhibition invites us to reflect on the persistence of images in our contemporary world.

The Musée Rath, a witness to Geneva's history, provides the backdrop for this exploration. Its neoclassical architecture reminds us of the legacy of the Reformation and its lasting influence on artistic representations

Bringing together a constellation of contemporary artists, the exhibition The Reappearing Image questions our relationship with tradition. By comparing works from the past and the present, it invites us to decipher the mechanisms by which iconographic forms and models reappear. Why do certain images manage to survive the passage of time and remain part of our collective imagination? "The forms used in the art of today can be seen in the art of the past; only context, intention and organisation make the difference", said the American artist Robert Morris. Echoing this statement, this exhibition highlights art forms and how they have evolved over time.

Origin

Conceived specifically for the MAH, this exhibition arose from an invitation from the museum itself to the ”la Caixa” Foundation, with which it maintains a close collaboration link. On several occasions, works of art from the vast collections of the MAH have traveled to exhibitions promoted by the Foundation, which manages ten top-level cultural and scientific centers in Spain.

On this occasion, the proposal is articulated through a selection of 18 works from the Contemporary Art Collection of the ”la Caixa” Foundation, the first private collection in Spain and one of the most notable in Europe. The reappeared image is based on a general look at the history of art and the history of the city of Geneva itself as the seat of Calvin's reform to address, ultimately, the use of the image in art.

Thus, the exhibition offers an unprecedented immersion in the way in which contemporary artists confront and reinterpret tradition and art history. How do you integrate or question them in your practice? The reappeared image, presented at the Musée Rath, brings together works whose link lies in the sovereignty of the image, that which supposedly should be venerated or which should be distrusted.

Trajectory

The Reappearing Image explores the different ways in which artists negotiate with the past: how do they integrate or deny art history and tradition in their practice? After a general introduction, the exhibition is structured around three thematic axes: "the survival of the image", "the dissolution of the image" and "the zero degree of the image - in the wake of Marcel Duchamp."

The tour begins with an installation by the American visual artist Mike Kelley (1954-2012) that evokes the capacity of images to subjugate us, the viewer. This is The Trajectory of Light in Plato's Cave (from Plato's Cave, Rothko's Chapel, Lincoln's Profile that occupies a large space in the central nave, an ancestral grotto reminiscent of Plato's cave inside a temple. He asks the viewer to submit to the work of art: “When you go caving, sometimes you have to stop, sometimes you have to get down on all fours, or even crawl... Crawl, you worm!” Visitors are asked to kneel and enter an imaginary cave. Their body is already captive.

The Survival of the Image

The exhibition then moves on to Survival of the Image, in which a selection of artists turn traditional religious scenes on their head. One of the first works in the exhibition is Vanessa Beecroft's Black Madonna with Twins (1969). The artist travelled to Southern Sudan in 2005 to document the colonial impact of the Church. In the works resulting from this trip, darkness conquers traditional Christian imagery, drawing on references to Italian Renaissance painting, although in this work the Madonna is situated in a precarious space of bare walls.

Beecroft has also confessed to being inspired by Pier Paolo Pasolini and, in particular, by the presence of the subaltern classes, who, as the protagonists of his cinematic dramas with a religious content, take on a new symbolic dimension. Like Pasolini's heterodox framings, Beecroft's images have an immediate iconic quality, and are visually striking because of their crudity and truth, and their break with traditional models. In the artist's own words, the work is “an ambivalent image capable of expressing both contentment and anger”.

Visitors then come across one of the self-portraits staged by the American artist Cindy Sherman (1954), in which she takes on various female roles that explore the concepts of identity and gender in relation to the conventions and fictions of our culture. This is Untitled no. 228. The feminist focus of the work is underpinned by the Old Testament story of Judith's beheading of Holofernes. The grotesque and over-the-top theatricality of Sherman's work, however, deepens and complicates this initial reading. The orchestration of the scenic elements leads us to believe that this is a tableau vivant, whereas Sherman's photograph does not refer to any specific work, but to different styles of artists from the past: we have seen this theme in Botticelli, Mantegna, Caravaggio or Artemisia Gentileschi, among others, and our memory deceives us into believing that we see them all in this image. The use of costume elements, make-up and prostheses also reveals an intention to underline the artificial nature of the image.

The exhibition also includes a triptych by Robert Mangold (1937), a master of minimalist painting. The artist has also turned to the art of the past, more in form than iconography: “The idea for the Curved Plan / Figure XI series came to me accidentally, after seeing a drawing by Pontormo that opened a door for me.” The work by the Florentine Mannerist painter is a 1518 sketch for a lunette fresco depicting the figure of Saint Cecilia. Pontormo was a true visual speculator, better understood by artists than by the public. In Mannerism, the sensuality of the lines became a hallmark of the period, representative of the moment when, at the Council of Trent, Catholicism was reasserting itself with new, more austere images, in response to the iconoclasm of the Reformation. This tension seems even more palpable in Mangold's work, which makes a radical return to the essentials, stripping the canvas of all representation to retain only its fundamental structure, a raw pictorial architecture.

In the same space, we can also see a work by the North American artist Jorge Pardo (1963), made up of fragments that accumulate in the unconscious, which appeals to our collective memory. Interested in modifying the meaning of everyday elements by altering them, the artist accumulates references here in a kind of mise en abyme. The background is based on René Magritte's paintings and is a found object: a fragment of the carpet designed by artist John Baldessari for the exhibition Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images, held at LACMA in Los Angeles in 2006. Pardo places a piece of his own work in the sky: a wooden crucifix from his project to design liturgical objects for the Catholic parish of Santa Trinitatis in Leipzig. The cross, which resembles an airship in association with the clouds, takes on a prosaic meaning. The celestial scene is thus situated between the sacred and the profane, highlighting the complex historical link between art and worship.

This space also features an oil painting by Spanish artist Darío Villalba (1939-2018): Gran caída II (after Peter Paul Rubens, The Fall of the Damned). Through a hybrid process combining photography and plastic intervention, Villalba transforms a detail from The Fall of the Damned into a unique work, on the borderline between reproduction and creation. At the heart of the Wars of Religion, patronage of the arts became a means of asserting one's faith. In commissioning this work from Rubens, the Duke of Neubourg was part of this dynamic, making the Last Judgement an allegory of his conversion. Behind Villalba's enigmatic stains lies a distant echo of a desperate act: the acid attack that mutilated Rubens' work in Munich in 1959. A little-known event that haunts the history of art. Villalba uses the now invisible scars of Rubens' work to evoke the memory of a traumatic event, while playing with the contemporary aesthetic of dripping.

The tour then continues with the triptych Crucifixion by Antonio Saura (1930-1998). Violence and realism are natural in Spanish Baroque painting. The generation of 20th-century artists to which Antonio Saura belongs found inspiration there. The artist, while drawing inspiration from his predecessors, offers us an interior and deeply personal vision of the drama, putting himself in the place of the suffering Christ. Saura's presence in this space is a veritable exhumation, an unexpected return to his Crucifixions, which made such an impact at his exhibition at the Musée Rath in 1989.

At the time, the artist wrote: “In the image of a crucified man, I have perhaps reflected my situation as a 'man without resources' in a threatening universe, in the face of which there is only the possibility of a cry. And on the other side of the mirror, I am moved only by the drama of a man (a man, not a God) absurdly nailed to a cross. An image that [...] can be a symbol of the tragedy of our times.”

La dissolution de l’image

This space highlights contemporary works that, beyond abstraction, question the margins of artistic creation by highlighting everything that surrounds the work of art or what remains after its cancellation, rejection or destruction: pedestals, frames, supports, languages... and so on. This emptiness, far from being insignificant, constitutes a genuine artistic stance, at once negating and reinventing the history of art.

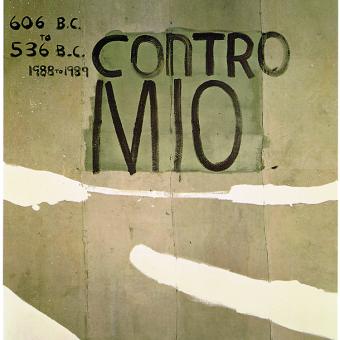

The work Contro Dio. Contro mio. Everyday is The Beast with Iron Teeth and Ten Horns. 70th Week by Julian Schnabel (1951). The artist overturns the codes of painting with bare canvases in which pictorial intervention is minimal, and words, creating a painting charged with apocalyptic meaning and pessimism. Military canvases sewn together, adding symbolic content: a tragic thread linking them to the lives of the soldiers who used them. The text in the works, meanwhile, heralds the apocalypse with various ancient references. The chronology of the captivity of the Jewish people in the new Babylonian empire, a symbol of moral decadence (606 BC - 536 BC), is associated with the artist's present (indicated by the dates 1988-1989). And, above all, a quotation from the visions of the prophet Daniel (7:7) which, through dark, zoomorphic allegories, presents various tyrants of late antiquity, associated here with the neoconservative, warmongering world of the 1980s.

The tour then moves on to a sculpture by the Spanish artist Cristina Iglesias (1956), --Untitled M/m 1-- which is ambiguous from its very conception to its presentation in a museum. It is an independent construction, both object and space, in which the limits of traditional sculpture are pushed back. It appeals to visitors through its open, ambivalent spaces, but in its studied dimensions, distances and gaps, the architecture it generates is inaccessible, like a traditional sculpture, like a sanctuary reserved for certain people. In its apparent intention to generate an architectural element, such as a curved wall or the rising start of a vault, the work seems to float between the built and the natural, the finished and the unfinished, inviting us to reflect on the very notion of construction and permanence.

Dora García (1965) is also represented here with her iconic sculpture Golden Bag. Dora García is known for her performative works that involve the public. The artist foregrounds elements such as the body or space and, in this case, she uses gold, an element that refers to purification and spiritual elevation, but whose dust is toxic, making the work one of her "dangerous actions".

Golden Bag also highlights something immaterial: space. Suspended from a corner of the exhibition space, it defies architecture by creating an enigmatic and inaccessible interior space. The image of a suspended fabric, treated as an untouchable object, may refer to textile relics, to the abundant paintings that depict them, or even to paintings in gold leaf. However, the image is not shown, nor is what is hidden behind the fabric. It is therefore an object that, somewhere between the theatrical and the sacred, signals above all an absence.

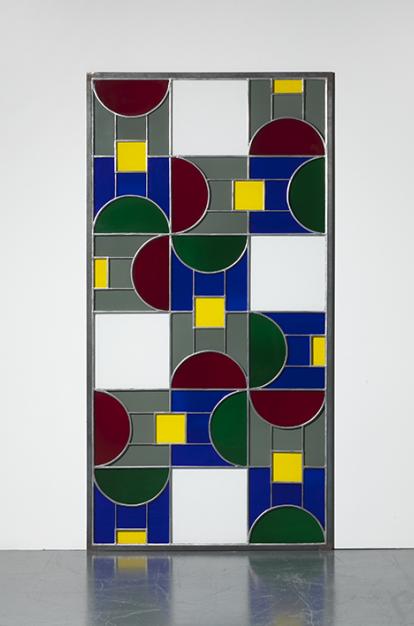

Metal-framed stained-glass windows by Matt Mullican (1951) are another clear example. Matt Mullican's work creates hierarchies in imagined constellations, parallel worlds across different languages. He is interested in signs, invented systems that conventionally replace or shape language. In this case, the language is abstract, geometric, and flat coloured. He encourages us to guess at a grammar, an order that makes it easier to read. In this case, the code takes the form of leaded crystal-stained glass windows, a technique particularly associated with places of worship. Although many of the images in Catholic stained-glass windows were destroyed during the iconoclastic fury, stained glass was one of the expressive languages recovered from temples after the Protestant Reformation, and it became more abstract, designed more to generate sensations than to tell stories. This sacred, but also secular, echo can be seen here, as these stained-glass windows are not raised but placed on the ground, denying their theatrical luminosity and bringing them closer to human space.

There is also an installation by Jan Vercruysse (1948-2018): the disappearance of any kind of representation, figurative or abstract, is the first thing that catches the eye in Eventail VIII. In the installation, only the auxiliary elements of the traditional plastic arts have remained: picture frames, pedestals for sculptures. The latter also appear to be silent spectators in front of the absent canvases, as they occupy a space that usurps the usual place for contemplating the paintings. By recognising these references, the viewer is forced to project his or her own content, to imagine the works that might be there, and even to wonder whether the works were once there and have now disappeared, or whether we are waiting for them to arrive so that they can take their traditional place. The result sought by the artist is paradoxical, since the attempt to attribute a specific meaning fails. Vercruysse offers the viewer a range of possibilities for attributing meaning to the work.

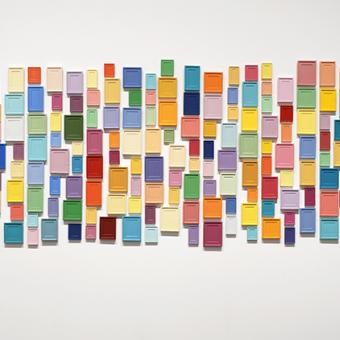

Collection of Two Hundred and Sixteen Plaster Substitutes by Allan McCollum (1944) can also be found in this space. In this work, plaster models of 216 paintings are presented according to the exhibition methods of nineteenth-century salons. To produce them, the artist systematised the artistic process into production stages: creating moulds, pouring plaster and applying enamel paint to create a monochrome surface. The result are moulds; “substitutes” for the original paintings, which in reality do not exist. Thus, “substitutes” that replace nothing.

These works evoke an iconostasis emptied of its sacred images, transformed into a silent setting for a reflection on the very nature of painting. By hijacking a religious symbol in this way, the artist questions our relationship with images and representation. By leaving us to face this void, he invites us to reconstruct the missing images ourselves, making us full players in his creation.

In the footsteps of Marcel Duchamp

The last space pays homage to Marcel Duchamp, a fundamental artist of art from the 20th century onwards. The art of the second half of the 20th century and the controversies surrounding the image cannot be understood without the controversial and provocative legacy of the French artist, who defined a whole way of confronting (or not confronting) images, of undermining art from within. However, late in life, Duchamp declared himself completely silent and unproductive until his death in 1968.

Duchamp was the patron saint of the paradigm shift in modern art, the great giant and authoritative image that artists had to confront, measure themselves against or leave, because the master had reached creative zero.

Considered the founder (in part to his great regret) of many of the creative veins of the twentieth century, he has been the object of reference for a large number of radical artists over the last few decades, who, overturning the artist's own approaches, from iconoclastic portraiture to appropriation, have left their mark, most often with the intention of challenging him and, on other occasions, paying him tribute. This is an artist who constantly forces us to revisit notions of the visible, the invisible, the tangible, the untouchable and the sacred, and who serves as an epilogue to this reflection on the image that returns.

This last space is dominated by the work of Duchamp (1887-1968) La Boîte en valise (série F), which belongs to the MAH collection. A reproduction of the revolutionary work Le grand verre can also be seen next to the work.

In 1934, Marcel Duchamp set about revisiting his earlier work. He conceived of a folding box to collect it and present it as a small museum, a kind of portable exhibition that could be carried around like a small suitcase. He produced several versions of this invention, which eventually became a kind of reproducible reliquary.

By reproducing his works in different media, on different scales and in limited editions, Duchamp demonstrated that the copy and the original offered comparable forms of aesthetic pleasure. He also redefined what constitutes a work of art and, by extension, the identity of the artist. This is just one of the many radically innovative and varied ways in which Duchamp was cited throughout his long career.

In relation to Le grand verre, the artist Sherrie Levine revisits Duchamp's work and, in The Bachelors (After Marcel Duchamp), transposes some of his characters (the so-called 'bachelors') into three-dimensional form, now enclosed in glass urns. In doing so, she raises a number of questions: what does it mean to transform the propositions of Marcel Duchamp's central work into objects? Is it a way of reifying his work as a relic, is it a tribute, a parody, a dethronement?

The showcases can be interpreted as a celebration of Duchamp, but also as an unmasking of the artist as a founding myth of modernity and his manipulation of certain traditional or religious devices. At the same time, the work questions the concept of authorship. These vessels become a kind of anonymous profane reliquary: whereas in Duchamp's case all the elements denote a complex optical, sexual and symbolic investigation, in Levine's work they become inert objects, but no less enigmatic for that.

On one side of this room, separated by arches, is the Portrait of Marcel Duchamp by the Spanish artist Concha Jerez (1941). The artist created a series of mental portraits whose subject is the name of a person, in this case Marc Duchamp.

It begins with the decomposition of the letters that make up the first and last name, and they end up materializing in a shapeless scribble. Behind this double gesture of writing are both the affirmation and the denial of an identity, a tangle inexpressible with verbal signs or with plastic forms. In the words of the artist: "For me the name of a person includes both the physical and psychological aspects, the experiences throughout the past time, but there are also the relationship possibilities that arise in the future time. […] When the sound of a person's name is emitted, the sound path traverses space and remains suspended in time. […] The result, logically, constitutes a tangle of strokes that are concrete letters, but that, when accumulated, produce forests of thoughts".

Portuguese artist Julião Sarmento (1948-2021) also makes a very direct allusion to Duchamp's Le grand verre in his work Phicares. Emptiness, eroticism, memory and appearances are key elements in Sarmento's work, as they were for Duchamp, to whom he refers explicitly in this altered version of the famous Le grand verre. Sarmento made a number of modifications: he rotated the work by ninety degrees, making it horizontal and revealing its landscape vocation, suggested by the finely drawn plant elements that humanise the famous cracks in the glass in Duchamp's work. The cloudy element on the left of the work is the one that crowned Le grand verre; it is one of the many symbols of desire (here accentuated by the floating lip leaves) that Duchamp referred to as the 'Milky Way'. This nomenclature provides the key to this tribute version: its title, Phicares, also refers to astronomy, since it is the alternative name of the constellation Cepheus, meaning “he who sets fire”.

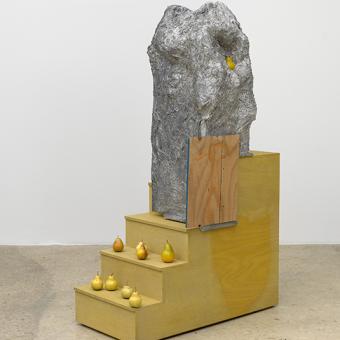

In the same room, a sculpture by the American Rachel Harrison (1966) refers to a seminal work by Marcel Duchamp: the famous Nu descendant un escalier no. 2 (1912), a painting that won the unanimous approval of avant-garde critics at the time. In this work, the artist reifies this image through a sculpture conceived as an accumulation: the ruin of an archaic kuros, which seems to have lost its corporeal human nature to become an indefinite mass, worn down by time.

Harrison's characteristic form-forms follow the idea of working with “forms that cannot be described”. Like an “anti-monument”, his kuros deprives us of its schematic anatomy and archaic smile, leaving it to our imagination to complete this lost form through our desire. And to do this, the artist gives us a few clues: the Duchampian staircase that suggests the descent from the figure's pedestal, the trompe-l'œil fruit, like a perennial life, and the design of the inverted feet that contradict the movement of the kuros.

In this room, right next to these works referencing Duchamp, is a sound installation, Studio Schwitters, by Czech artist Pavel Büchler (1952) which, through 78 loudspeakers, offers readings of the phonetic poem by one of Duchamp's contemporaries, Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948). Entitled Ursonate (1922-1932), the voices reading the poem sound simultaneously from megaphones that visually represent the sequences of letters that make up the poem. The computer programme on which the synchronisation of the voices and the sound of the devices is based makes the original language of Schwitters' composition, which was originally a purely phonetic poem devoid of meaning, even more incomprehensible and abstract. In this way, Büchler transforms the entire piece into an incomprehensible Babel that takes us back to the role of text in the sphere of ritual and the problems posed by its interpretation.

In this way, the figure of Duchamp, who was also interested in the deconstruction of language, is incorporated, as a sound framework rather than an imaginary one, with this reference to Kurt Schwitters as the artist co-responsible for Dada, perhaps the most relevant movement in 20th century art when it comes to the fantasy of getting rid of all images.